Endless green meadows, much like the endless ocean, may seem monotonous. With the naked, untrained eye, you won’t easily see variation in these landscapes. Except perhaps for the waves or the differences in the height of the grass. This perception is not necessarily rooted in reality, but rather in a lack of knowledge. Agricultural scientist Lenora Ditzler and researcher and architect Janna Bystrykh embarked on a quest to explore the narratives of the peatlands during their residency at the Veenweide Atelier, and were gripped by the story of grass and meadows. We spoke to Lenora Ditzler about the project.

The gap between the narrative of farmers and policy makers

“Initially, we visited the area for a week-long program, during which we met and spoke with various locals: farmers, but also landscape historians and ecologists,” Lenora explains. This first step was followed by a series of interviews with academic experts. “Our goal was to gain an understanding of the context in which people live and work in this area.” While Lenora and Janna initially took paludiculture (a form of agriculture for re-wetted peatlands) and the existing plant list of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) as their starting point, the conversation quickly widened. They learned that possible futures with higher water levels in the peat meadow landscape can also include herb-rich grasses, differentiation between seasonality of fields, and new narratives around soil health, meadow birds, and biodiversity.

“For example, the CAP list mentions some plants that farmers could cultivate as part of paludiculture,” Lenora explains. “Cattail, cranberries, wild rice. But in practice, very few of the farmers we spoke to actually cultivated these plants or were genuinely interested in doing so.” Additionally, their conversations with ecologists and historians revealed that these plants had never been part of the peat landscape and therefore not part of its ecological legacy. In these conversations, we kept coming back to the importance of history and historical knowledge in shaping a sustainable story for the future of the peatland.

Cropscapes

The constant in the narrative of the peatland turned out to be the meadow. Instead of cattail or cranberries, several farmers here are engaged in a different type of wetland agriculture: managing their grassland in a way that maintains the high water level (40 cm is the province’s desired level) and biodiversity. But just as regulations are often imposed top-down, rather than developing them from the farmer’s perspective, one plant, such as grass, is also not often taken as a starting point when thinking about the larger landscape. “At least not outside of science,” says Lenora. “For us, it was exciting to do just that, and to scale up from the level of plants to landscapes and policy levels.”

This was the starting point of their project Cropscapes, to map the herb-rich meadows of various farmers in the peatlands. Specifically, they highlighted the meadows of three farmers, with land adjacent to each other. These are farmers who farm on ‘old grass’ and who have not ploughed their herb-rich grassland for decades, one of them even since the 1970s. Fields that have not been ploughed to create perfectly flat pastures or arable land, and still have some of the old markings of elevations in the landscape. Lenora: “Farmers here were already adapting their farms to the changing water levels 200 years ago. These are farmers who still do things the old-fashioned way. All the while, they also take into account new ecological and agricultural knowledge about farming and biodiversity. They support the birds, soil health, and insect life in their farming management practices.”

Farming wisdom

According to Lenora and Janna, the wealth of knowledge that farmers have about their grasslands, crops, and the (meadow) birds and animals that live there, needs to be utilised and elevated when shaping a future scenario for the peatland. “The livestock industry on wetlands will of course have to be much less intensive,” Lenora admits. “But even this grassland can still be suitable for dairy or meat production. In addition, biodynamic or organic products also fetch a higher price on the market.” Using part of the land for a different type of crop from the CAP list is also an option. “All these combinations need to be explored to find realistic paths. And not every farmer is a pioneer. Some will first wait and see which way the wind blows, and only follow later.”

Connecting and visualising

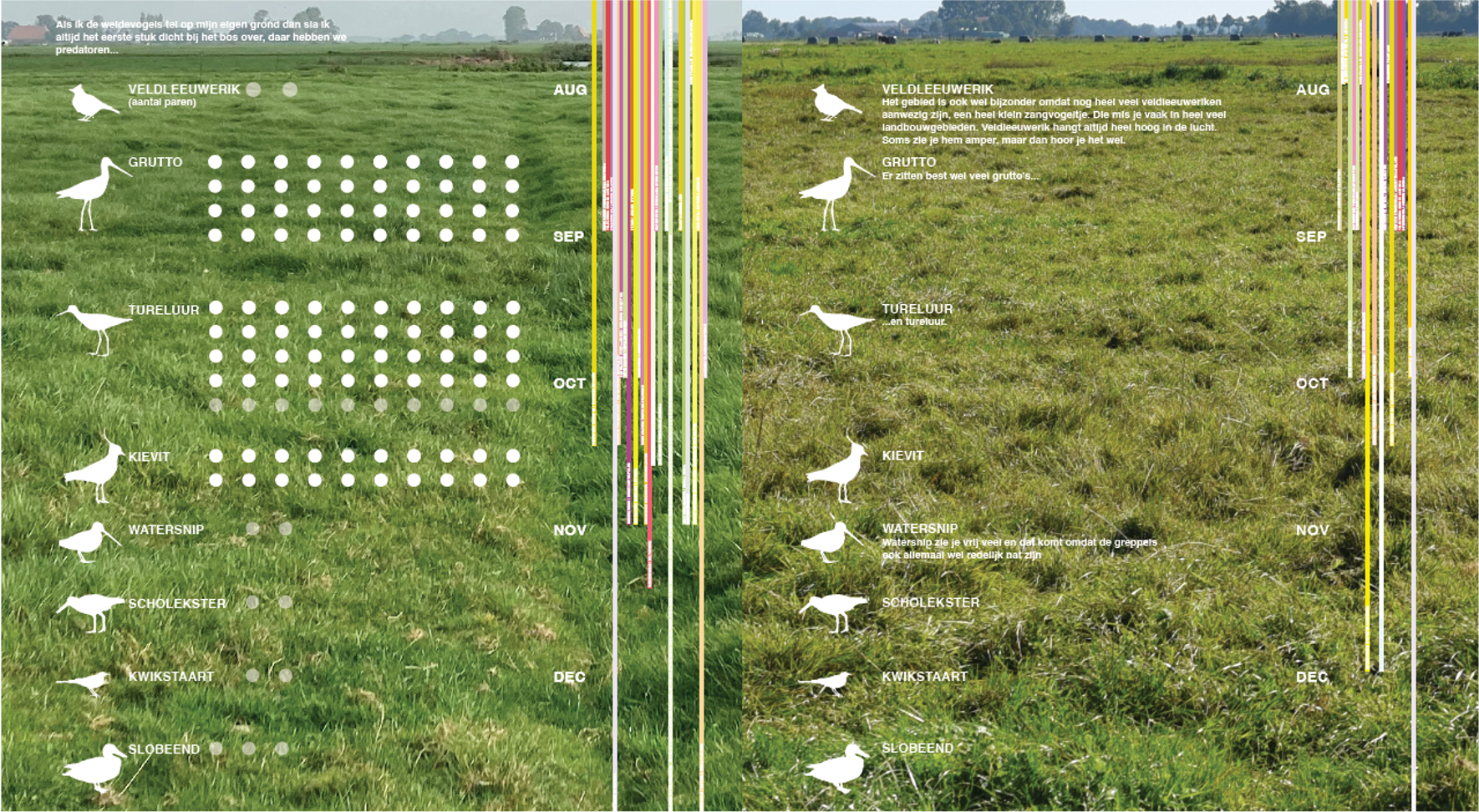

As part of this initial exploratory phase, the team developed a visual map with facts and figures related to three different sites: one intensive farm, and two “old grass farms”. These maps explore meadow bird populations, grass types and flowering periods, types of farming operations, and water levels, and are supported by quotes and stories shared by the farmers in the field. They see their project developing further in different forms and media. “We would love to share the historical and contemporary knowledge on peat meadow grasslands more broadly and emphasise the role of the farmer in imagining productive futures for this area.”

Lenora and Janna look forward to the further development of the Veenweide Atelier and see huge potential in the collaboration between different designers. “I’m very excited about the establishment of a physical place for encounters and research for designers and stakeholders,” says Lenora. “Coming together, discussing ideas, and viewing designs makes imagining and visualising something new more enjoyable and easier.”